from

Plant Diseases: Their Biology and Social Impact.

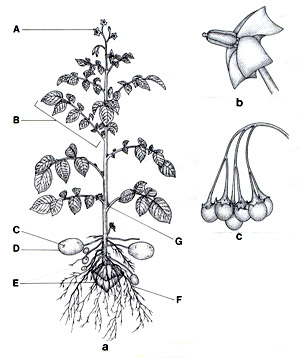

The Potato Plant

A field of growing potato plants is a beautiful sight, especially in midsummer when the plants begin to bloom. The leaves are usually composed of a number of dark green leaflets. Sometimes the lowest leaves are composed of a single blade that connects to the main stem by a leaf stem called the petiole. In the angle between the stem and the petiole is a tiny bud that can grow into a side branch. There is also an apical bud at the highest growing point of the plant. The hormones produced at the apex inhibit the growth of the lateral buds, a phenomenon known as apical dominance. If the top of a plant is pinched off, apical dominance is eliminated, and the lateral buds begin to grow. This is a common practice to produce bushier house plants or other ornamental plants.

Most of the leaves of a potato plant are divided into leaflike sections or leaflets that all connect to the petiole. Such leaves are compound and, in the potato plant, consist of an odd number of leaflets. When leaves are not divided into leaflets but whole, like those of a maple tree, they are called simple. Buds are present where the petiole of a leaf meets the stem, but not where leaflets connect to the petiole. There should never be any confusion about whether a leaf is simple or compound once the location of the bud is determined.

The presence of flowers on potato plants may not be familiar to those who have not seen potato fields. They are similar to those of the tomato, a close relative, but they vary in color depending on the cultivar and can range from white to deep purple. Potato flowers consist of a single pistil surrounded by five pollen-producing stamens within a set of five fused petals. After blooming, fertile plants produce green berries similar to a small tomato and filled with numerous tiny seeds.

| Table 1-1. Top Food Crops of Developing Market Economies(^a) |

|

Energy Production |

Protein Production |

Crop |

Megajoules

of Edible Energy |

Crop |

Kilograms Produced

per Hectare per Day |

| Potatoes |

216 |

Cabbages |

2.0 |

| Yams |

182 |

Dry broad beans |

1.6 |

| Carrots |

162 |

Potatoes |

1.4 |

| Maize |

159 |

Dry peas |

1.4 |

| Cabbages |

156 |

Eggplants |

1.4 |

| Sweet potatoes |

152 |

Wheat |

1.3 |

| Rice |

151 |

Lentils |

1.3 |

| Wheat |

135 |

Tomatoes |

1.2 |

| Cassava |

121 |

Chickpeas |

1.1 |

| Eggplants |

120 |

Carrots |

1.0 |

| (^a) Source: Potato Atlas. 1985. International Potato Center (CIP), Lima, Peru. Used by permission of the CIP. |

The potato is in the botanical family Solanaceae, which includes the tomato as well as eggplant, green and red pepper, tobacco, petunia, and some poisonous members such as deadly nightshade. The similarities in flower structure make the relation between these plants clear even though they are quite different in other characteristics. The name is derived from the Latin solamen which means "comforting," reflecting the sedative effects of some of the alkaloids produced by some members of the family. Deadly members of this family slowed the acceptance of the edible members as food plants, but eventually they were discovered to be safe. Related alkaloids are present in the leaves of potato plants, causing digestive upsets to those who eat them. If potato tubers are left in the light, they too will develop green color and alkaloids and should not be eaten. The Solanaceae family is worldwide in distribution, but some members, such as tomato, tobacco, and potato, are native to South America and were unknown to Europeans before they began their explorations of the New World.

The familiar starchy "potato" is actually a tuber as reflected in the plant's Latin name, Solanum tuberosum. All organisms are given a similar Latin binomial (two-word name) based on a system created in the 1700s by the famous Swedish naturalist, Carolus Linnaeus. The first word is the genus, a name shared by closely related organisms. Other plants in the genus Solanum are closely related to the potato but sufficiently different to be considered different species. The second word is the specific epithet, a descriptive word that separates this species from all others in that genus. Because the words are Latin, they should be italicized or underlined. Once the genus has been written out fully, it can then be abbreviated, when repeated, by the uppercase first letter followed by a period and the specific epithet, as in S. tuberosum. A species was once defined as organisms that would produce fertile offspring if mated, but our expanding knowledge of the variety of life has made this definition difficult to apply in the case of many microorganisms. In such cases, species names change as our understanding of the relationship between organisms improves.

At about the same time as potato plants begin to flower, small swellings start to develop at the ends of underground stems called stolons. These swellings are the new tubers, which store the excess food the plant produces during photosynthesis. The starchy tubers may be harvested and eaten at any time. The small, freshly harvested "new potatoes" are tender and delicious, but, to maximize yield, most potato growers wait until later in the season to harvest the potatoes. As the mature vines die above ground, the tubers develop an outer cork layer for survival in the soil during the winter. This layer also protects them from desiccation (drying out) and wounding when they are harvested and put into storage. Stored potatoes must be kept cool to prevent rotting by bacteria and fungi present on the tubers. They also need to be kept in the dark to prevent "greening" of tuber tissues.

Because tubers grow underground, they might appear to be roots, as carrots are. Closer examination reveals that the eyes are really buds in the axils of tiny scalelike leaves. Roots do not produce buds and leaves, so tubers are actually underground stems adapted to storage of nutrients. After several months in storage, the buds begin to sprout. Apical dominance, as described earlier, can be observed on tubers as well as on aboveground stems. Because the buds at the apex of a tuber produce hormones that inhibit growth of lower buds, the sprouts are most developed at the apex of the tuber.

Most commercial potato growers and home gardeners do not plant the tiny seeds from the green berries produced after flowering. Potatoes are grown by vegetative propagation; that is, small tubers or pieces of tubers are planted. To maximize their planting stock, farmers may cut the tubers into several pieces. Each piece can grow into a new plant as long as an "eye" is present. Tuber pieces that do not have an eye are called "blind" and will not grow into a new plant. The cutting of tubers also releases the lateral buds from apical dominance, so that each eye may produce a plant.

Fig. 1-7. The potato, Solanum tuberosum. a, Diagramatic illustration of an entire plant: A, flower; B, compound leaf; C, "eye"; D, tuber; E, tuber piece used for planting; F, roots. b, Flower. c, Fruits (berries).

Vegetative propagation has several advantages. The tuber pieces, known as "seed" to farmers, contain substantial food reserves, so that a vigorous, green shoot pushes up through the soil more quickly than does the shoot from a tiny seed. In addition, each tuber piece grows into a plant that is genetically identical to the parent plant in color, taste, maturity, and other important characteristics. True botanical seed, from the fruit of a plant, is the product of sexual reproduction, which results in genetic variation. Each seed produces a plant that is slightly different from all of its siblings. Genetic uniformity is a great advantage when uniformity has an economic benefit, as in flowers, fruits, and ornamental plants, so vegetative propagation has become a common practice in modern agriculture.

There are, however, some disadvantages to vegetative reproduction. The advantages of uniform characteristics may be outweighed by the disadvantage of uniform susceptibility to pests and pathogens. If one plant in a field can be destroyed by disease, then so can all of its neighbors. Genetic uniformity increases the risk of loss. A second important risk lies in the large pieces of plant tissue that are planted during vegetative reproduction. Rather than a tiny seed, cuttings, roots, tubers, bulbs, and other relatively large plant pieces may be planted. These large plant pieces often carry pathogens, especially viruses and other systemic parasites, into the planting area at the very beginning of the season. The yield and quality of the crop may be greatly reduced due to their presence.

Of course, many kinds of parasites were not discovered or well understood until relatively recently, but farmers of the past observed the ravages of the diseases they caused. Farmers suspected that reduced yields were related to the use of vegetative reproduction which, despite its convenience, was considered "unnatural." Periodically, they allowed the plants to reproduce sexually, "the natural way," and harvested the seeds to begin new selections for acceptable plants. They believed that sexual reproduction restored the vigor of their weakened plants, when, in fact, the seeds had simply escaped infection by the pathogens present in the parent plant.

Only small collections of potatoes were brought from the New World in the early days of European potato production, and, from these tubers, further selections were made in an attempt to find potato cultivars suitable for consumption. As a result, the genetic variation among the potato cultivars was very limited. Crop losses occurred every year from various causes, and occasional food shortages were not unusual. When crops were good, tubers were plentiful in the months after the harvest, but as the winter months passed, supplies diminished and the tubers began sprouting, ready to plant for the next crop. The summer months were a hungry time, usually requiring the peasants to spend what few coins they had for grain to feed themselves until the next potato harvest.

Introduction

The Arrival of the Potato in Europe

The Potato Plant

The Components of the Epidemic

The Birth of Plant Pathology

Protecting Potatoes from the Blight

Lessons from the Potato Famine

Selected Readings

RETURN TO APSnet FEATURE STORY