Richard Zeyen, Emeritus Professor, and

Carol Ishimaru, Professor and Head,

Department of Plant Pathology, University of Minnesota

Marty Dickman, Director, Institute for Plant Genomics and Biotechnology, and

Christine Richardson, Professor, Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology,

Texas A&M University

doi:10.1094/APSFeature-2009-12

"Whoever could make two ears of corn or two blades of grass grow where only one grew before, would deserve better of mankind than the whole race of politicians put together."

—Jonathan Swift

Dr. Norman Borlaug, the world’s most renowned agriculturalist, passed away on September 12, 2009, at his home in Dallas, TX. He was 95.

Norman Ernest Borlaug was thrust onto the world stage in 1970. That year the Nobel Peace Prize Committee selected him to represent a decades-long, science-based international agriculture improvement and educational effort. This revolution in agriculture had greatly increased the world’s food supply largely by improving crop plants and fostering science-based agricultural education. This massive, historical improvement was labeled "The Green Revolution" because it dealt with chlorophyllous plants.

The 1970 Nobel Peace Prize Committee believed the Green Revolution had fostered peace. In their opinion it helped millions escape famine and misery, had averted massive social and political upheaval, and brought prosperity to areas of the world heretofore considered hopeless.

The work for which Norman Borlaug was recognized began in 1943. In that year he had accepted the challenge of a plant pathology/wheat improvement position in a joint Rockefeller Foundation/Mexican Government-sponsored agricultural improvement program in Mexico. Borlaug then selected and led the group, stationed in Chapingo, Mexico, that produced disease-resistant, widely adapted, and high-yielding wheat varieties. These wheats not only made Mexico self-sufficient in wheat production in the late 1950s, but were transposed to Latin America and south Asia. The Mexican wheats and successful agricultural education initiatives in India and Pakistan made those countries self-sufficient in wheat production by the early 1970s. These were the achievements that formed the basis of the Nobel Committee’s choice of Norman Borlaug.

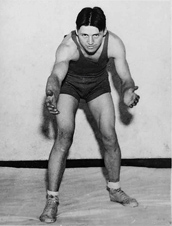

Born in 1914 on a remote farm near Cresco, Iowa, Norman Borlaug was a good student. He was an energetic, enthusiastic, and compassionate young man, and an all-around high school athlete. He came to the University of Minnesota in 1933 to wrestle and prepared to teach high school science and coach athletics. He was an undergraduate in the College of Forestry where, in 1937, he received his B.S. degree. As a college wrestler, he caught the attention of Professor Elvin C. Stakman, himself a former high school athletic coach. Professor Stakman greatly admired Borlaug’s dedication, mental toughness, and uncanny persistence.

| |

Norman Borlaug in 1936:

a Big Ten wrestler at 145 lbs. Photo from the Department of Plant Pathology, University of Minnesota archives. |

|

|

|

As an undergraduate Borlaug had attended a talk by Stakman about stem rust of wheat. He was very impressed with both the science and the charismatic speaker. After earning a B.S. degree in Forestry, Borlaug, on the promise of a job with the U.S. Forest Service, married Margaret Gibson, an education major at the University of Minnesota. Margaret was the sister of George Gibson, an All-American guard and captain of the university’s football team. The Forest Service job was withdrawn due to financial constraints, and the young couple was left in a dire financial situation.

Borlaug got up his courage and approached professor Stakman about a graduate assistantship, which would help the young couple financially. Stakman, acting as the Director of Graduate Studies, expressed displeasure at Borlaug’s motives. He would rather have had a burning desire for graduate work in plant pathology as a spoken motive. Nevertheless, Stakman accepted Borlaug into an M.S. program in Plant Pathology at Minnesota. Borlaug’s graduate advisors were former Stakman students and great teachers: Professors Clyde M. Christensen and Jonas J. Christensen. Borlaug researched box elder wood deterioration caused by Fusarium for his M.S. degree (1941) and Fusarium wilt of flax for his Ph.D. (1942). Borlaug took a position with the DuPont de Nemours Company and moved to Delaware while in the process of writing his dissertation.

Meanwhile, in 1941 the Rockefeller Foundation, at the urging of Vice President Henry Wallace, asked professor Stakman and a small team of scientists to determine what could be done to make Mexico self-sufficient in food production. After spending months touring Mexico, the team recommended a trial agricultural assistance program in conjunction with the Mexican Government. Stakman recommended his talented and bilingual former graduate student Dr. J. George Harrar to direct the Rockefeller portion of the joint program. Later, in 1943, when the fledgling program needed a plant pathologist and wheat breeder, Harrar, as Mexican based program director, and Stakman, as Rockefeller Foundation consultant, recruited Borlaug, even though Borlaug had no wheat experience. They knew the conditions in Mexico were very primitive but that Borlaug was "just the man" for the job. Stakman, who admired Borlaug’s intelligence, stamina, and determination, stated it clearly: "He will not be defeated by difficulty and he burns with a missionary zeal."

Thus Stakman and Harrar persuaded Borlaug to leave his secure position at DuPont, and begin the wheat program at a very dilapidated one-building experiment station near Chapingo, Mexico.

Borlaug knew the greatest constraint to wheat production in Mexico was stem rust disease. It would do little good to breed wheat only to have it destroyed by Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici. Thus, stem rust resistance breeding was a high priority. He selected his Mexican associates and taught them to cross, breed, and grow wheat. They collected stem-rust-resistant wheat from any source they could find. Together they made thousands and thousands of crosses during the summers at Chapingo, near Mexico City, and did the same in the winter at irrigated plots in the Sonoran Desert near Obregon, Mexico. This revolutionary high volume "shuttle breeding" tactic yielded two generations of wheat per year. It was a large, massive program. It was said that if Borlaug’s experimental rows of wheat were planted back-to-back they would stretch 400 miles!

This revolutionary shuttle breeding/high volume program speeded the identification of stem rust-resistant wheat progeny with excellent yields and qualities. Quite by accident, they produced plants that could thrive in Mexican summers and in winters at distinctly different locations and elevations. In contrast to the existing breeding dogma, these "Mexican wheats" lost day length sensitivity and in doing so were widely adaptable. However, when fertilized, these new wheat varieties grew tall and lodged in high winds and rain.

| |

Norman Borlaug and J. George Harrar (Director of the Rockefeller Foundation’s portion of the "Mexican Program"). These tall, rust-resistant wheats had one problem: they often lodged before harvest. Stronger-strawed wheats were needed. Harrar later became President of the Rockefeller Foundation. Photo circa 1950 in Obregon, Mexico. Compliments of the University of Minnesota. |

|

So, beginning in 1954 Borlaug crossed his disease-resistant, high-yielding wheat varieties with dwarf wheats from Japan. The progeny were short, stiff-strawed and high-yielding and maintained excellent disease resistance. Seed of this wheat was grown in farmer’s fields side by side with their traditional varieties. Farmers saw what could happen in their own fields and rapidly adopted these varieties. The seed for these wheats was freely given to anyone who visited the Mexican program regardless of national origin or politics. Soon these wheat varieties were spread throughout Mexico and into Latin America. At the same time, a new race of wheat stem rust called 15b had formed in Iowa. Race 15b exploded on the North American Great Plains causing catastrophic losses in wheat and barley. In response, Borlaug teamed with public and private scientists from Canada, the United States, and other nations. Together this cooperative effort resulted in the incorporation of strong, durable resistance to race 15b and adequate resistance to other stem rust races. These resistant backgrounds were bred into the Mexican wheats and found their way around the world.

| |

|

|

Norman Borlaug and one of the many stem rust-resistant, semi-dwarf wheat varieties his group pioneered in the Rockefeller/Mexican government program. The stem rust resistance used to combat race 15b and most existing races was eventually deployed throughout the world. Now, 40 years later, this heretofore relatively durable resistance has succumbed to the Uganda 99 family of wheat stem rust races. |

|

By 1959 Borlaug thought his mission finished. The peril of stem rust race 15b was overcome and Mexico’s wheat production had quadrupled. The original goal was met. Mexico was self-sufficient in wheat production and Mexican scientists were trained to carry on. But, raging famines in Pakistan and India soon became the new focus for these "hunger fighters." The Mexican wheat varieties proved their day length insensitivity and geographical adaptability, because they performed just as well in Pakistan and India, as they had in Mexico. Now the Rockefeller Foundation along with the Ford Foundation and others were asked by the governments of Pakistan and India to help repeat what had been done for Mexico.

After a precarious beginning, Pakistan and India tripled wheat production and reached their goals of self-sufficiency by the mid 1970s. In The Population Bomb (1968) Paul Ehrlich wrote it was "a fantasy" that India would "ever" feed itself. But by 1974 India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. Pakistan progressed from harvesting 3.4 million tons of wheat annually when Borlaug arrived to around 18 million today, and India went from 11 million tons to 60 million. In both nations food production since the 1960s has increased faster than the rate of population growth.

Imitation is a sure sign of success. In 1960 Harrar and the Rockefeller Foundation, with help from the Ford Foundation, had used the "Mexican Program" and its associated training philosophy as the template for the formation of the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. Soon, other international crop research centers were formed. An unprecedented revolution in science-based agriculture had exploded upon the world scene. These achievements in applied biology and agricultural education, coupled with worldwide financial support for international crop improvement centers (now allied as CGIAR) accelerated the Green Revolution. Borlaug’s educational hands-on, long days in the field, philosophy was the backbone of the international training programs at CIMMYT and eventually at all international crop centers. He was an apostle and evangelist for wheat. He said simply that "wheat is the best teacher about wheat" – you plant it, watch it grow daily, live with it – then you begin to learn about wheat.

Thus, the Green Revolution was as much about graduate level, hands-on training and learning as it was about disease-resistant, high-yielding, and broadly adapted varieties. All this passed relatively unnoticed in affluent countries like the United States, but in developing and underdeveloped countries it literally changed their world.

Borlaug always considered himself to be a teacher, as well as a scientist. Today, thousands of men and women agricultural scientists from more than 50 countries are proud to say they were Norman Borlaug's "students."

Borlaug’s employment at CIMMYT in Mexico finally ended in 1981, but he remained a consultant throughout the remainder of his life. In 1984, at age 70, he became a Distinguished Professor in International Agriculture at Texas A&M University and taught a one semester course each year. In 1986, he joined former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Nippon Foundation of Japan, under the chairmanship of Ryoichi Sasakawa, to develop an African agricultural initiative. Over a 20-year period, the Sasakawa-Global 2000 agricultural program, has worked in 15 African countries to transfer improved agricultural technology to several million small-scale farmers. This work, with added assistance from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, continues today.

Borlaug realized that he was the only agriculturist to ever receive a Nobel Prize. There may never be another since there is no Nobel Prize for agriculture. Therefore, he played a central role in establishing the World Food Prize in 1986. Based in Des Moines, Iowa, the World Food Prize is considered the "Nobel Prize" for food and agriculture. In true Norman Borlaug fashion the World Food Prize Foundation also developed outstanding educational programs to engage young people in world food issues.

Borlaug always acknowledged his many "comrades in arms" who contributed their talents to the vast undertaking of fighting hunger and rural poverty. In his 1970 Nobel Lecture, he stated:

"When the Nobel Peace Prize Committee designated me the recipient of the 1970 award for my contribution to the 'green revolution,' they were in effect, I believe, selecting an individual to symbolize the vital role of agriculture and food production in a world that is hungry, both for bread and for peace. I am but one member of a vast team made up of many organizations, officials, thousands of scientists, and millions of farmers - mostly small and humble - who for many years have been fighting a quiet, oftentimes losing war on the food production front."

He also clearly understood that, without curbs on human reproduction, gains in agriculture would not solve every ill, but rather buy only a few decades of time. In the same 1970 address he stated:

"We must recognize the fact that adequate food is only the first requisite for life. For a decent and humane life we must also provide an opportunity for good education, remunerative employment, comfortable housing, good clothing, and effective and compassionate medical care. Unless we can do this, man may degenerate sooner from environmental diseases than from hunger.

"And yet, I am optimistic for the future of mankind, for in all biological populations there are innate devices to adjust population growth to the carrying capacity of the environment. Undoubtedly, some such device exists in man, presumably Homo sapiens, but so far it has not asserted itself to bring into balance population growth and the carrying capacity of the environment on a worldwide scale. It would be disastrous for the species to continue to increase our human numbers madly until such innate devices take over. It is a test of the validity of sapiens as a species epithet."

Norman Borlaug truly became a citizen of the world. He was a tireless advocate for the impoverished and disadvantaged. He worked with world leaders to eliminate hunger and poverty and to promote education. When in 1999 a new family of wheat stem rust races arose in Uganda (Ug99), Borlaug used his influence to bring attention to this threat to world food production. The international complacency that had followed the success of the Green Revolution began to lift, leading to the formation of the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative in 2005.

Borlaug’s successes were based on hard work, scientific imagination, and dedication – as well as many sacrifices made by family. Nevertheless, even with a very hectic travel schedule, he made a point of being present for major family events. In the early years in Mexico, Borlaug coached his son’s neighborhood baseball club, and was later attributed with playing a major role in bringing little league baseball to Mexico. His athleticism and enthusiasm for sports remained a constant in his life. During visits to the University of Minnesota, Borlaug always made a point of visiting his good friend J. Robinson – the UMN wrestling coach! The honor Borlaug brought to that sport was recognized by his induction into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame & Museum as an Outstanding American in 1992. Beyond all of his incredible accomplishments, Norman Borlaug, the man who saved millions from starvation, was also one of the most caring and humble of human beings.

In the years preceding his death, Borlaug was often honored for a lifetime of service and for the sacrifice and hardships he endured. Humbly he accepted awards, like the Congressional Gold Medal below, and used his visibility as the voice for those who have no voice.

The world’s respect for Norman Borlaug, and what he and those involved with the Green Revolution accomplished, cannot be over stated. He was held in the highest esteem. Norman Borlaug joined Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Elie Wiesel, and Martin Luther King Jr., as one of only five people in history to have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal.

According to his daughter, Jeanie Borlaug Luabe, Norman Borlaug’s last thoughts and utterances concerned the plight of African farmers. As long as he drew breath, Norman Borlaug never ceased to be concerned for the impoverished and hungry of the world.

Additional Information and Resources:

The Nobel Foundation

Norman Borlaug, The Nobel Peace Prize 1970

The Mathile Institute & Hunger Fighters

Freedom from Famine − The Norman Borlaug Story

University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology

Norman Borlaug - Plant Pathologist/Humanitarian

University of Minnesota News Service

A Tribute to Norman Borlaug

The Norman Borlaug Heritage Foundation

normanborlaug.org

The World Food Prize

Norman E. Borlaug: Founder

Durban House Publishing

The Man Who Fed the World (book by Leon Hesser)

Bracing Books: Borlaug

Volume 1: Right Off the Farm, 1914-1944

Volume 1: Wheat Whisperer, 1944-1959