Keywords:

Fungal Pathogens, Diseases in Natural Plant Populations, Biology, Techniques

Abstract

Plants make up 80% of our food, but up to 40% of global food crops are lost to plant pests and diseases each year according to the United Nations FAO . Scientists try to mitigate disease impacts by identifying microscopic pathogens such as fungi and running experiments to study their traits and how they affect plants. In this module, students build on previous knowledge of ecosystem interactions and energy flow by learning about pathogenic fungi that consume plants. Students may be familiar with edible mushrooms and the role of fungi in decomposition, but this module highlights another major ecosystem function of fungi—agents of plant disease. This module synthesizes broad concepts in biology and ecology with an emphasis on agricultural implications. Students collect diseased leaf samples from around their neighborhood, culture their own fungal species, and explore the diversity of fungi that infect local plants. Students learn sterile technique, microscopy, and other lab skills central to microbiology, as well as practice writing predictions, collecting data, and analyzing trends to grow their skills as scientists. This hands-on exploration of the world of fungi gives students an exciting and concrete first experience in microbiology research.

Fig. 1.

Fungal Fighters lab module.

|

Unit Overview

Lab Summary

This module is intended for high school students with some introductory background in ecology and a little laboratory experience. The Fungal Fighters lab (Fig. 1) engages students in an exciting tournament as they learn how fungi interact with each other and with plants. Students practice microbiology lab technique by isolating and culturing pathogenic fungi from diseased leaves to learn about fungal traits. They then calculate the growth rates of their individual cultures and measure the competitive ability of their fungal culture against those of their classmates. To learn more about microscopic fungal structures, students also look at their fungal species under a microscope. Instructors should familiarize themselves with mycology terminology (refer to lesson plan for glossary of terms) and sterile technique in preparation for teaching this module.

Learning Goals

- Understand and describe the impacts of fungal diseases on plants, from an individual plant to plant populations and ecosystems

- Learn skills for microbiology research: sterile technique, culture isolation, and microscopy

- Practice making observations on an organism's traits

- Practice collecting data and analyzing results using mathematical tools

- Practice developing informed and testable hypotheses

Biological Concepts

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Life Sciences standards supported by this lab module are Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics and Matter and Energy in Organisms and Ecosystems. Students first learn about the different life strategies fungi use to acquire energy from plant hosts (García‐Guzmán and Heil, 2014). In the lab, students isolate and culture necrotrophic fungi—plant pathogens that kill hosts and obtain nutrients from dead matter. In agriculture, global food security is heavily impacted by crop losses due to disease (Savary et al., 2012). Through a discussion of plant diseases in agriculture, both at local and global scales, students can see how plant pathogens also can affect plant communities and ecosystem function. Optionally, instructors may choose to highlight examples of local plant diseases of concern or the work of local researchers and discuss career paths in plant health or mycology.NGSS Cross Cutting Concepts addressed include Cause and Effect; Scale, Proportion, and Quantity; and Structure and Function. The module begins with students learning how to recognize diseases in plants and then how to isolate the pathogenic agent that is causing the disease. Students learn how fungi cause plant diseases by infecting, colonizing, killing, and consuming leaf tissue. In addition, during the contamination activity in Lab Procedure Part 1 students learn how to practice sterile technique and how it affects the success of their cultures. In Lab Procedure Part 2, students learn how to isolate fungi from plants and maintain cultures. In Lab Procedure Parts 3 and 4, students take distance and area measurements of fungal growth, observe competitive outcomes between pairs of fungi, and quantitatively interpret results, supporting scale, proportion, and quantity. Finally, in Lab Procedure Part 5 students learn to look at fungi and identify their main structures using microscopy, revealing the fascinating diversity of these microscopic organisms.

Implementation

This module has been taught in a 9th-grade biotechnology class in the Central Valley of California, an important agricultural region. Each student maintained and worked with their own fungal sample over the course of four weeks. In the module introduction, it is important to relay that while the lab activity is based on individual leaves and, subsequently, individual fungal species, disease research happens at scales from microscopic to landscape. At this high school, we specifically emphasized how researchers at nearby universities use the methods in this lab activity to investigate plant diseases in California agriculture. Beyond the learning goals, we sought to bolster science identity and engagement with personal investment in asking genuine scientific questions. Knowing that they would later be competing against each other, students were personally invested in growing and understanding their fungal cultures.The classroom was made up of around 30 students working in groups of 4. Each class period was typically split into three time periods: lecture/topic introduction, lab activity, and worksheet completion (Table 1). In our classroom, each table group had an open computer to check off steps on the procedure. Instructors gave a visual demonstration of the lab procedure at the start of class, and we projected visual demonstrations of each procedural step on the main screen of the room throughout the lab activity. Alternatively, instructors could print out paper copies of the procedure for students to follow. Worksheets could be worked on simultaneously with the lab activities, with additional dedicated time at the end of each class period to complete each day's section. While students were responsible for completing their own work, they were encouraged to deliberate on worksheet questions together.

Table 1. Suggested schedule

|

| |

Block Period 1 |

Block Period 2 |

Week 1

| Lab overview/introduction | Plant diseases discussion |

| | Pour agar plates | Plate diseased leaf tissue |

| Week 2 | Isolate pure culture of fungi | Check fungal growth |

| | | Start fungal fight matchups |

| Week 3 | Measure final growth and complete growth-rate section of worksheet | Assess group fight winners and set up final matchup(s) |

| Week 4 | Microscopy | Final matchup assessment

|

Lab Procedure

Part 1—Introduction to Sterile Technique

Before growing fungi in pure culture, students prepare plates of agar growth medium to use for the remainder of the module and learn about practices of sterile technique and contamination. (Materials required are listed in Table 2.) Instructors should mix and autoclave media before class and leave bottles in a warm water bath during the module introduction. First, students should put on personal protective equipment (PPE) and clean their workbench, adopting this practice for the remainder of the lab module. Gloves are the most necessary piece of PPE, but teachers may elect to require aprons and goggles for their class. Students remove petri plates from the plastic sleeve, open the lid slightly, carefully pour in a layer of liquid media, and close the plate as quickly as possible. To emphasize the necessity of the sterile technique, students deliberately contaminate a plate by leaving the lid open too long or touch the media with used gloves. At the start of the next lab, students should note the fungal growth(s) on contaminated plates. After the media in the plates has cooled and solidified, students use the contaminated plates to practice sealing petri plates with Parafilm. The remaining plates are stored in the original plastic sleeve for the following classes.

Table 2. Consumable materials needed

|

|

Section |

Materials |

Costs |

| Sterilization | Beakers | $100 |

1 of each item per group

| Tea strainers | $16 |

| 70% ethanol | $40 |

| | 10% bleach | $10 |

| Metal probe | $40 |

| | Ethanol burner | $200 |

Agar plate materials

| Malt extract powder | $90 |

| 1 bottle of media per group | Agar powder | $50 |

5 plates per student

| Glass media bottles | $160 |

| | Sterile petri plates | $180 |

| | DI water | |

| Culturing | Tweezers/forceps | $56 |

| 1 of each item per group | Scissors | $64 |

| Parafilm and Sharpie markers shared with the class | Parafilm | $24 |

| | Sharpie markers | $20 |

| Microscopy | Microscope slides | $27 |

| 1 of each item per student | Coverslips | $9 |

| Eyedropper | $6

|

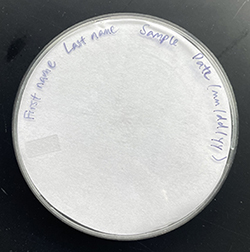

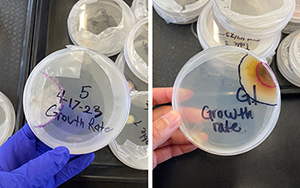

Fig. 2. Properly labeled plate. Fig. 2. Properly labeled plate.

|

Fig. 3. Fungal inoculum placed in the center of an agar plate. Fig. 3. Fungal inoculum placed in the center of an agar plate.

|

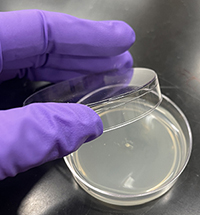

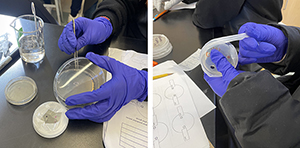

Fig. 4. Students demonstrating proper lab techniques when transferring fungal culture (left) and sealing a plate with Parafilm (right). Fig. 4. Students demonstrating proper lab techniques when transferring fungal culture (left) and sealing a plate with Parafilm (right).

|

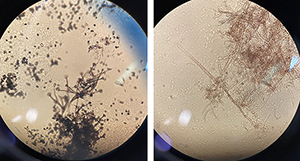

Fig. 5. Growth-rate plate outlines after 3 days of growth (left) and after 7 days of growth (right).

|

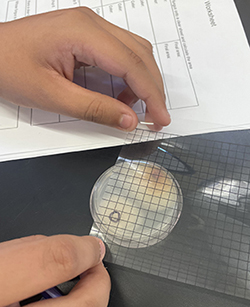

Fig. 6. Student calculating fungal growth using a transparent grid overlay. Fig. 6. Student calculating fungal growth using a transparent grid overlay.

|

Fig. 7. Fungal cultures under the microscope at 40X magnification. Fig. 7. Fungal cultures under the microscope at 40X magnification. |

Part 2—Isolating Fungi from Plants

Each student is responsible for isolating and maintaining their own fungal culture throughout the module, but four students work together in groups to share materials and compare fungal cultures. Diseased leaf samples can be collected by students or brought in by instructors. To maximize the diversity of fungal species in the classroom, students should collect samples from a range of plant species. Closely following the procedure document, each student cuts a subsample of their leaf, surface sterilizes it, places it on their agar medium plate, seals it with Parafilm, and labels the plates for storage (Fig. 2). (Materials required are listed in Table 2.) Over the next few days, the fungi will grow out of the leaf and into the agar. From this plate, students make observations and then isolate pure cultures on two new plates. For the isolated culture plate, the inoculum is placed in the center of the agar media (Fig. 3). For the growth-rate plate, the inoculum is placed on the agar media near the edge of the plate. Throughout the module, students will repeat the procedure for handling sterile agar plates and live fungi, improving their technique (Fig. 4).

Part 3—Measuring Growth

One fungal trait students measure is growth rate. In this section, students practice collecting and analyzing data. Students use a marker to outline the perimeter of the fungal culture on the bottom of the Petri plate after 3 and 7 days, depending on the school class schedule (Fig. 5). (Materials required are listed in Table 2.) The distance from the original inoculum point to the fungal perimeter is the total growth. Using the growth distance and days since culture transfer, students calculate growth rates in millimeters per day and graph distance over time in their worksheets. Instructors should emphasize the concept of rate, distance grown over time, which is graphically represented as a slope. In this section, it is recommended that instructors check in with students one at a time. As a class, compare the total distances grown and growth rates on a shared document or graph.

Part 4—Fungal Fights Competition

The most exciting part of the module is the “fungal cage fights," where pairs of students place inoculum on opposite sides of a small agar plate and have their fungi compete against each other. Based on observations of the growth patterns of their fungi and those of their classmates, students make informed predictions about who will win. Students are surprised to find that the fast-growing species might not always win, and slower-growing species may have traits that make them better competitors. To set up fights, students label and record plate matchups between all combinations in their group, making sure to keep track of which students' cultures are on each plate. Students may use different color markers to mark inoculum points or write their initials on each side of the plate. After one week, the fungi will have grown enough to meet each other in the middle of the plate. Students measure the growth area for each fungus by placing a transparent grid sheet over the plate, tracing the shape of the fungus mycelium, and calculating the area based on the number of filled grid squares (Fig. 6). Students determine the winner for their group. Instructors may continue setting up more fights bracket-style to determine a class-wide winner if desired.

Part 5—Microscopy

To appreciate the structural diversity of fungi, students look at fungal structures under a microscope. (Materials required are listed in Table 2.) Prior to genetic tools, fungal species were traditionally identified by their microscopic structures; instructors can ask students to imagine how taxonomists could categorize such superficially simple organisms. Slides may be prepared in class with the protocol provided here or by an instructor beforehand. Preparing slides in class allows students to look at their own cultures, as well as learn new techniques in flame sterilization and slide mounting. Alternatively, instructors can choose to set up stations to exhibit a diverse set of known structures. In our implementation, we chose to bring in slides of different colors, shapes, and sizes (Fig. 7). The main structures to discern are hyphae, conidiophores (spore-producing structures), and conidia (asexually produced spores). After looking at each slide using the microscopes, regroup as a class to identify and label structures.

Evaluation

Students are assessed on lab procedural techniques, understanding of biological concepts, and calculations. Throughout the lab, instructors should monitor students for skills such as sterilization, culture plating, and organization. These skills can be evaluated as points for completing each day of the lab. The worksheet incorporates terms and definitions related to lecture material, justifying predictions based on evidence, and calculations performed on collected data. The worksheet prompts can be used to assess students' understanding of scientific concepts, focusing on evaluating the observations, predictions, and result statements for the lab module.

Conclusions

Over the course of this module, students developed a foundational understanding of plant disease ecology. Most notably, students became increasingly comfortable and precise in their lab skills, particularly those relating to sterilization and culture transfer. By reiterating the basic concepts of microbiology lab techniques each week, the class reduced cases of contamination over time and could confidently advance to more complex experimental setups with smaller plates and multiple inocula. This helped ensure the success of the exciting “fungal fights" portion of the module. Through monitoring the student groups, we saw students make detailed observations and collect precise measurements on their isolated cultures. This data was then used to form testable hypotheses on fungal fight outcomes. In addition to mastering laboratory skills, students learned about the diversity of fungal plant pathogens and their impacts on plant communities. Through the lecture material, students connected the lab activity to plant disease ecology at multiple scales. We shared how ongoing research at local institutions is studying the population and community dynamics of plant pathogens. By the end of this module, students developed confidence in their microbial lab skills and a strong understanding of how researchers use these skills to tackle conservation and agricultural issues.

Resources

References

García‐Guzmán, G., and Heil, M. 2014. Life histories of hosts and pathogens predict patterns in tropical fungal plant diseases. New Phytol. 201:1106-1120.

Savary, S., Ficke, A., Aubertot, J. N., and Hollier, C. 2012. Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Secur. 4:519-537